GRE Issue Essay Template: 30-Minute Outline → Clear, High-Scoring Draft

A practical 30‑minute Issue essay template that matches the current GRE: decode the instruction set, map paragraph roles, plug in examples and counterarguments, and use a simple editing pass to deliver a clear, defensible draft under time.

GRE Issue Essay Template: 30 minutes to a clear, high‑scoring draft

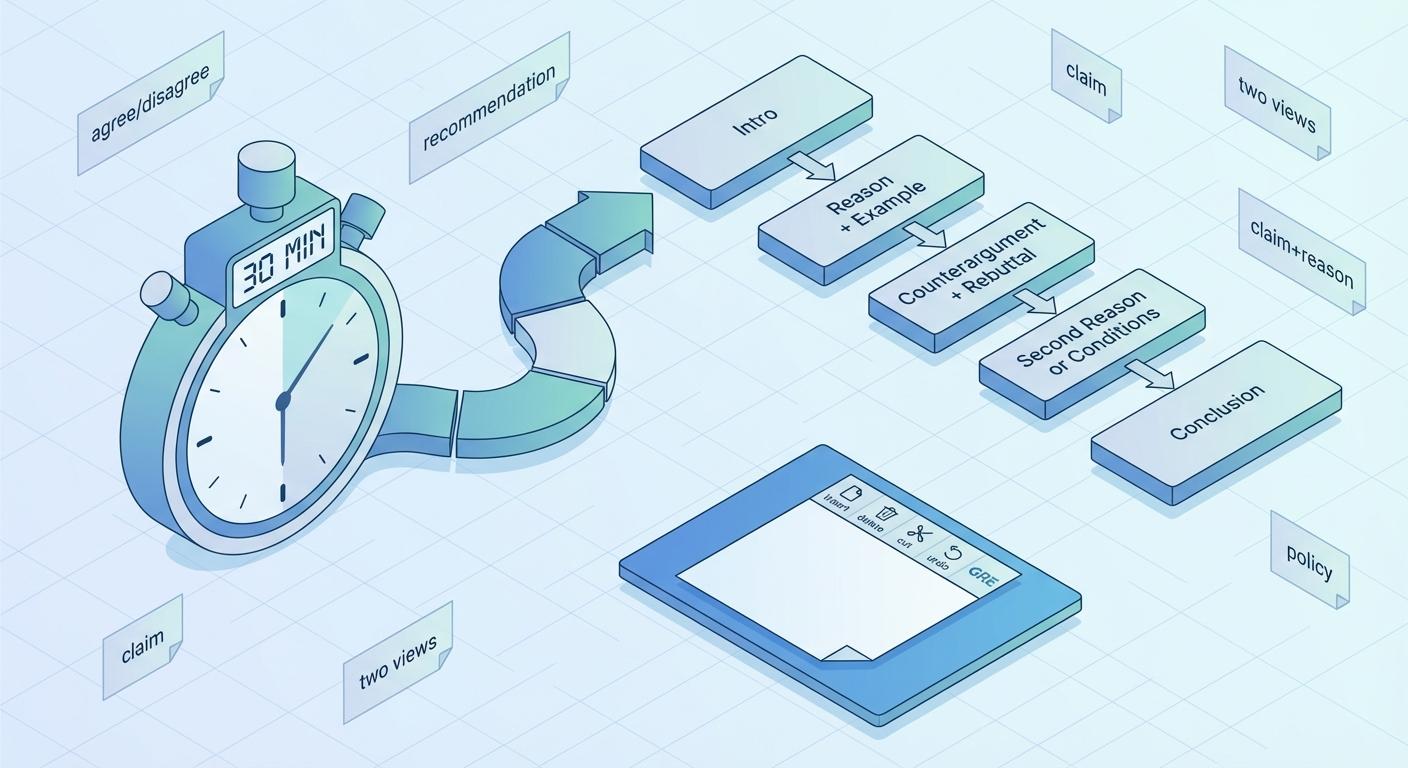

On the current GRE General Test (updated September 22, 2023), Analytical Writing consists of one 30‑minute “Analyze an Issue” task, appears first, and there’s no scheduled break during the test. Your essay is typed in a basic word processor with only insert, delete, cut‑and‑paste and undo—no spellcheck or grammar check. The score scale remains 0–6 in half‑point increments. This article gives you a fast outline, the role of each paragraph, and a plug‑and‑play system for examples and counterpoints so you can turn any prompt into a crisp, defensible essay in half an hour.

What high scorers do differently

Strong Issue essays stake out a clear position, develop it with well‑chosen reasons and examples, address the prompt’s exact instructions, and maintain logical organization and precise language. Length matters far less than clarity, development, and control. Think in terms of purpose: every sentence should either advance your claim, deepen your reasoning, or acknowledge and handle a plausible counterpoint.

Your 30‑minute, no‑panic plan

Use this clock to structure your work: 0–2 minutes: Decode the instruction set; define the task in your own words. 2–5 minutes: Choose a position; craft a one‑sentence thesis that mirrors the instructions. 5–9 minutes: Outline two reasons, one counterpoint you’ll address, and plug in specific examples. 9–10 minutes: Jot a quick paragraph map. 10–24 minutes: Draft the essay, paragraph by paragraph. 24–29 minutes: Revise for clarity, relevance to the instructions, and flow. 29–30 minutes: Proofread for obvious errors and strengthen the last line.

First 3 minutes: match the prompt to its instruction set

Every Issue topic comes with one of these tasks. Identify it immediately so you answer the question asked: Agree/Disagree with a statement: take a stance and note where it may or may not hold. Recommendation: argue when adopting it would or would not be advantageous. Claim: take a position and address compelling challenges to that stance. Two views: pick a side but explicitly discuss both perspectives. Claim + reason: analyze both parts—do you agree with the claim, the reason, or only one? Policy: take a position and explore likely consequences and trade‑offs.

Minutes 3–5: commit to a focused, defensible thesis

Write one sentence that mirrors the instruction and scopes your argument. Example: While expanding public data access generally improves accountability by enabling independent scrutiny, it risks undermining privacy when access lacks guardrails such as tiered permissions and anonymization. The thesis signals your stance, your core reasons, and your sense of conditions.

Minutes 5–9: outline the backbone

Decide on two reasons that directly support your thesis and list the specific example you’ll use for each. Choose the counterpoint you’ll acknowledge and how you’ll respond to it. Note the condition under which your position might change; this adds nuance. Keep bullet notes short: R1 + Example, R2 + Example, Counter + Rebuttal, Condition.

Paragraph roles at a glance

Intro (2–4 sentences): Frame the issue, state your thesis in instruction‑mirroring language, preview reasons or conditions. Body 1 (6–8 sentences): Reason 1 → specific example → why the example matters → link back to instructions. Body 2 (6–8 sentences): Either Reason 2 with a different example, or Counterargument + Rebuttal if the instruction emphasizes weighing views. Optional Body 3 (4–6 sentences if time): Conditions or limits under which your stance shifts. Conclusion (2–3 sentences): Synthesize the through‑line and restate the thesis with the key condition; avoid introducing new examples here.

Plug‑and‑play sentence starters

Intro: The claim that [restate briefly] is persuasive to the extent that [qualifier]. I contend that [position] because [Reason A] and [Reason B], although [key condition] matters. Body topic sentences: First, [Reason A] because [causal mechanism]. A concrete illustration is [specific example]; in this case, [salient facts]. This matters because [tie to outcome or principle the instruction cares about]. Counter + rebuttal: Admittedly, critics argue that [counterpoint]. Yet this view overlooks [rebuttal mechanism], especially when [condition]. Condition paragraph: My claim holds when [context], but weakens if [trigger], because [mechanism]. Conclusion: Ultimately, [restate position] best addresses the prompt’s demand to [echo instruction], provided that [condition] is kept in view.

Build an example bank you can use on any prompt

You don’t need dozens of facts; you need a handful of versatile, analyzable cases. Organize yours into broad domains and write two lines for each: what happened and why it supports a reasoning pattern. Reliable domains: Technology and privacy or access; Education and learning outcomes; Public policy and incentives; Business and markets; Science/health and trade‑offs; Environment and externalities; Culture/media and information quality. Example blueprint: Remote work policies increased flexibility and access to talent (benefit), but degraded mentorship and innovation for some teams lacking structured collaboration (trade‑off). This case supports arguments about policy design needing guardrails and context.

Five counterargument patterns that elevate your score

Feasibility: The idea is sound but unrealistic given resources or time. Distributional effects: Benefits are uneven; who bears costs? Unintended consequences: Incentives shift and create perverse outcomes. Causation vs correlation: The evidence cited doesn’t prove the mechanism. Time horizon: Short‑term pain may lead to long‑term gain (or vice versa). Pick the one that best matches the prompt and your examples, then neutralize it with a concrete mitigation or condition.

Draft quickly, revise deliberately: a 5‑minute polish

Run a simple 4‑3‑2‑1 check. 4 links: Does every paragraph explicitly link back to the instruction language? 3 transitions: Add or sharpen three signposts (for example, however, therefore) to make logic visible. 2 sentences: Shorten two long sentences for clarity. 1 upgrade: Swap one vague noun (things, issues, aspects) for a precise term. Finally, scan for obvious typos and subject‑verb agreement—there’s no spellcheck on test day.

Common pitfalls and how to dodge them

Echoing the prompt instead of taking a position: put your thesis in your own words and commit. Listing claims without analysis: after every example, add one sentence that explains what the example shows. Ignoring the instruction set: paste key instruction verbs into your first line of notes and keep them on‑screen while drafting. Overstuffed intros: keep context to two sentences, then plant your thesis. New examples in the conclusion: synthesize instead.

A 7‑day micro‑sprint to lock it in

Day 1: Build a 10‑item example bank across the domains above. Day 2: Two timed outlines (10 minutes each), no drafting. Day 3: One full timed essay using the template. Day 4: Review your essay against the rubric points in this article; rewrite the intro and one body paragraph for concision. Day 5: One timed essay with a different instruction set than Day 3. Day 6: Two more 10‑minute outlines emphasizing counterarguments. Day 7: Final full timed essay; compare it to Day 3 to confirm tighter thesis statements, sharper example analysis, and cleaner conclusions.

Using Exambank alongside this template

Exambank can make this process lighter without taking over your writing. Use the diagnostic to free up time: let the platform identify Verbal and Quant weak spots so you can allocate 30 focused minutes to Issue practice most days. Mine examples from reading: the Learn and Solve Together flows expose you to GRE‑style arguments and scenarios that translate neatly into essay examples; save two per session. Train the reasoning moves: select short practice blocks that involve assumptions, cause‑effect, and inference—these sharpen the exact analysis you’ll write in Body paragraphs. Keep yourself consistent: streak tracking and predicted trajectories encourage daily 30‑minute sprints instead of sporadic long sessions. Review smarter: after a week, glance at your analytics to spot themes (for instance, you rush conclusions or underdevelop counterpoints) and plan the next micro‑sprint.

One‑page recap you can memorize

- Identify the instruction set. 2) State a thesis that mirrors it. 3) Outline two reasons and one counter you’ll neutralize. 4) Draft with paragraph roles: Intro → Reason + Example → Counter + Rebuttal → Second Reason or Conditions → Conclusion. 5) Revise with the 4‑3‑2‑1 check. If you stick to that flow, you will deliver a coherent, defensible essay under real testing constraints.